Although some claim that the police as a whole are good, and any problems are the fault of a few individuals, recent events seem to suggest otherwise.

Historically, members of the BAME community have faced discrimination, and their past experiences, both personal and public, are not encouraging for their faith in the integrity of law enforcement or the court system.

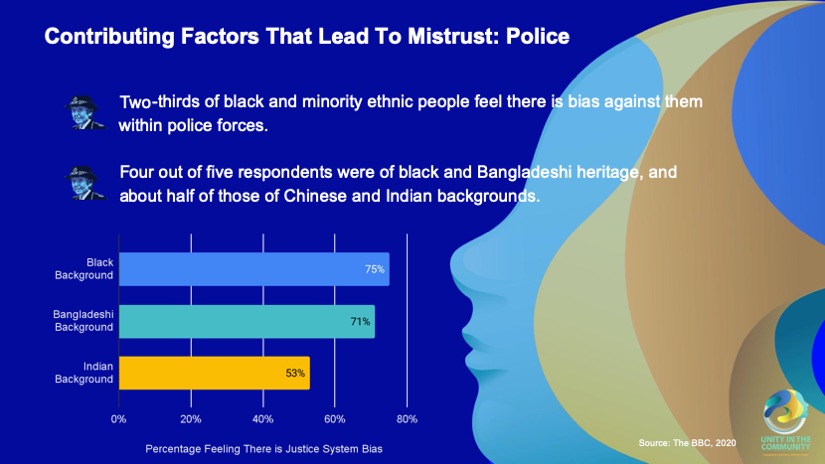

According to a BBC survey, up to two-thirds of black and minority ethnic people believe the police are biased against them.

Of the respondents, a majority of four out of five were of black or Bangladeshi heritage, while half were either Chinese or Indian.

The BBC survey also indicated in this chart that three quarters of black communities, 71% of Bangladeshi communities and 53% of Indian communities feel they are treated more harshly in court.

And although research conducted by Hope Not Hate found that the majority of respondents do not believe the police are complicit in systemic racism, the greater BAME community have a different perspective, and believe that significant levels of systemic racism have been endemic within the force.

Research has also revealed widespread anger about the government’s handling of the coronavirus pandemic, and feelings of political alienation.

All these factors reiterate and highlight the importance of initiating a dialogue that delves into the BAME community’s perspective in order to work towards providing a viable solution to systemic mistrust.

Despite the findings of a report by a commission on race and ethnic disparities claiming that institutional racism doesn’t exist, lived experiences by Black, Asian and Minority communities say otherwise. Prejudice exists in the health service and the data displaying health inequalities between different ethnic groups evidence this. Several health professionals have spoken about the structural racism in the UK.

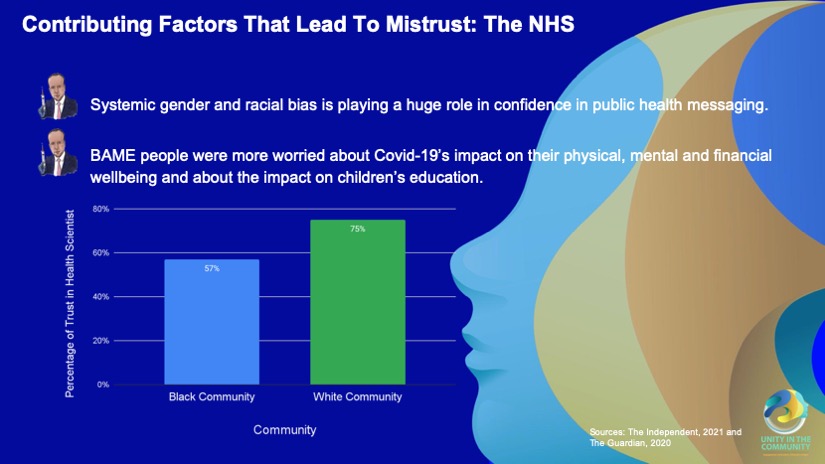

Looking at things from an intersectional lens, it is evident that systemic gender and racial bias is a playing a huge role in the confidence in public health messaging. Prior experiences of facing discrimination within the NHS appears to be affecting people’s perceptions of the reliability of any messages surrounding the vaccine. To understand how starkly different the confidence levels are, it is worth looking at this table which depicts the percentage of people from both the black and white community trust in messaging from health scientists. Whereas people from a white background have 75% confidence, only 57% of people from a black background trust these officials.

Black, Asian and minority ethnic people trusted government scientists and public health officials less than white people did at the height of the UK’s coronavirus outbreak, according to a study that raises fresh questions about the pandemic’s disproportionate impact.

Furthermore, research has shown that people from Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic communities were more worried about Covid-19’s impact on their physical, mental and financial wellbeing and about the impact on children’s education.

As you delve further into health inequalities in the UK, you start understanding more why vaccine hesitancy exists and a lack of trust in the NHS. Trust needs to be built, and in order to improve confidence levels amongst all ethnic groups, it’s important to recognise and address health inequalities.

Lord Wooley who is a crossbench member of the House of Lords said in February this year mistrust in the Government is one of the reasons for vaccine hesitancy in the bame community.

He said: Boris Johnson’s government has shown a blindside to the depth of race inequality that if unchecked will cause a generation of mistrust that will only worsen.

Of most concern is the lack of trust in our government and agencies including the NHS.

This lack of trust isn’t exclusive to the present government but is historical – there has been a certain amount of scepticism that BAME communities have held about democratic and civic institutions because of the deep seated structural race inequalities that have never been fully acknowledged, much less dealt with.

Covid has exposed the government’s reluctance to accept the racial inequality fault lines but rather than deal with the blinding obvious, it has thrown its cheerleaders, including, Dr Tony Sewell, and Dr Raghib Ali to offer an alternative. Dr Sewell wrote: “Structural Racism doesn’t explain why black people are more likely to die from Covid”. Instead, he went on to strongly suggest we should look to genetics, and no doubt a Black inferiority gene rather than social determinants to explain why more Black people are disproportionately dying of Covid-19.

In his government report for the Race Disparity Unit, Dr Raghib Ali,said ‘structural racism had no bearing on BAME Covid deaths’.

Too often the government and its cheerleaders view those who want to highlight and tackle the deep-seated structural inequalities as those who are ‘wallowing in victimhood’.

The Downing Street line is to ‘change the narrative’.

Given this stance and the historical pessimism BAME communities hold towards political institutions and their associated authorities, is it really any wonder that the level of cynicism is as it is?

Click on the buttons below to find out further information for the other 2 individual webinars.